Chapter 18: The Regime at Mid-Passage 1950-1959

"By 1950 the regime had taken mature form. Despite the tenseness of its relations with hard-core monarchists, the system that Franco had developed was much more like the blueprint laid down by Calvo Sotelo and the Acción Española theorists for “instauration” of an authoritarian monarchy than it was the fascist formulas of the Falange. All seven main points of Acción Española theory had been met: the legislation of 1947 had converted the system into an authoritarian monarchist state; a controlled corporative parliamentary system had been in place since 1943; economic policy was based on state dirigiste neocapitalism; labor relations were administered through state corporative syndicalism; since 1945 the Movimiento had been deemphasized (though far from eliminated); the system relied on the ultimate political support of the military, who had initiated it; and religious, cultural, and educational policy had developed an elaborate structure of “national Catholicism” that provided more effective support than did any remaining fervor for the Falangist program.

Serious pressure for further liberalization had come to an end, and though Franco was still persona non grata to social democratic western Europe, the domestic opposition had begun to despair of his overthrow. It had been unable to maintain any consensus of its own,"

"Franco remarked privately late in 1949 on the subject of his recent visit to Portugal and Salazar's advice to him: “Salazar said that because Spain was entering a constituent period, 1 should concede some greater liberty to the country. 1 shall give Spain no further liberty during the next ten years. After that period, I will relax my hand somewhat.”*? Although there is no indication of any specific plan or timetable, that was about the way things worked out, and there were no significant changes until later in the new decade. "

"west European governments remained more hostile to the regime than did Washington. Their resumption of intercourse did not bring with it full political or military acceptance as distinct from the technical proprieties of normal diplomatic, commercial, and financial relations. Francos first nominee as new ambassador to the Court of St. Jamess, Castiella, was rejected because of his “fascist” background and publications hostile to England. Ironically, the subsequent candidate accepted by London was Miguel Primo de Rivera, whose fascistic credentials were presumably superior to those of Castiella. The continuing hostility of west European governments was only meagerly balanced by the friendship of many Latin American countries? and of the Arab states of the Middle East, the latter having supported the regime in the United Nations and used Spain as a source of arms purchases."

"When a Spanish diplomat was dispatched to Mexico at the beginning of 1950 to explore possible restoration of diplomatic relations, he was promptly murdered by a gunman reported by Mexican police to have been an agent of the Spanish Communist Party.* Normal relations were not restored until after the death of Franco."

"Within Spain, living standards were finally improving more rapidly, and this, together with the obvious failure of the opposition, helps to explain the quiescent atmosphere of the 1950s, though one major disturbance did take place in March 1951. In Barcelona, discontent with continuation of rationing and low wages first found expression in a boycott of public transport to protest a new fare increase, and then quickly mushroomed into a mass industrial strike. "

"On July 10 the Conde de Barcelona addressed a letter to Franco declaring that with such outbursts the regime could not expect to continue as it had for the past twelve years. He also pointed to widespread corruption and what he defined as the need for major economic improvement and foreign assistance, proposing that he and the Generalissimo work together for a new political solution of conciliation.* This of course implied signifi- cant liberalization and a more concrete plan for restoration, but Franco was not impressed.” He intended simply to shut the lid more firmly, which in fact had been done even before the royal letter arrived."

"he never publicly overreacted, whether to a rash of strikes, a monarchist manifesto, a minor street demonstration, or a rare shouted insult by an old guard Falangist. His tendency was to trivialize and isolate each act of defiance rather than to generalize or inflate it, thus making them all seem to be petty irritants. In this way he was able to avoid adding to any momentum they might have generated."

Strategic Rehabilitation: The Pact with the United States

"Once a regular relationship had been established with the United States, it developed rapidly in the climate of the Korean War. The official ex- change of ambassadors took place early in 1951, the oily Lequerica taking over the embassy in Washington, where interest in bringing Spain within the United Statess defense network was mounting...west European democracies, who refused to hear of Spain joining the new NATO organization as long as the Franco regime lasted. "

"Nonetheless the integration of Spain into international organizations continued. Spain entered the World Health Organization in 1951, UNESCO in 1952, and the International Labor Organization in 1953, while Franco once more offered a Spanish contingent for Korea. During a Middle Eastern swing in the spring of 1952 Martin Artajo suggested the alternative of a southern tier defense alignment consisting of Spain, Italy, Greece, and several Arab states to defend the Mediterranean basin in conjunction with NATO. This ploy failed to prosper, but negotiations with the United States did, leading eventually to three executive agreements that made up the Pact of Madrid signed on September 26, 1953. These provided for mutual defense and military aid to Spain, the construction and use of three airbases and one naval base in Spain for a ten-year period, and economic assistance. The form of an executive pact was adopted because unlike full treaties this would not require ratification by the United States Senate, where residual opposition from liberals would have been an obstacle. In addition to direct military and economic assistance, Spain received significant credit and the opportunity to buy large amounts of American raw materials and surplus foodstuffs at reduced prices, and the volume of American capital investment in Spain notably increased. Official American figures place the value of all forms of American economic aid (including credits) over the next ten years at 1,688 million dollars, to which was added 521 million in military assistance.*” The figure might have been higher had not Spanish authorities slowed negotiations during 1952-53 in order to concentrate on the new Concordat with the Vatican. Once the Korean War ended, the value of the Spanish connection declined somewhat. Nonetheless, though the amount of aid was considerably less than other west European countries had received through the Marshall Plan, its impact was considerable"

"When United States Air Force Secretary Talbott indicated that atomic bombs would be kept in Spain, this touched off protest even within the regime. Though the fact was denied, it was widely suspected that the pact con- tained additional secret clauses permitting such procedures. An addi- tional secret agreement did exist, stipulating that the United States could determine unilaterally when it would use the bases to counter “evident Communist aggression, though the bases were officially under joint Spanish and American sovereignty.!' "

"This was followed two years later, in December 1955, by Spain's admission to the United Nations as part of a package deal. By 1956 relations had even thawed with the new leadership of the Soviet Union, which repatriated about 4,000 Spanish nationals, mostly former child evacuees of the Civil War and relatives of Republican emigrés but also including a hundred or so captive veterans of the Blue Division who had survived thirteen or more years in Soviet prison camps.

The Spanish government then moved to the offensive as an injured victim of imperialism. An annual Gibraltar Day had already been designated for the Frente de Juventudes, and in 1956 the Spanish delegation formally presented to the United Nations Madrid's claim for the devolution of Gibraltar, a suit that would be pressed with increasing though fruitless vigor for nearly two decades.

Franco began to have second thoughts about the regimes new international relations only after the successful Soviet launching of Sputnik in 1957. This was widely taken as evidence of major Soviet breakthroughs in missile delivery systems, and Franco had a healthy, even exaggerated, respect for the achievements of the Soviet system of dictatorial order. Fear that the nearby American airbase at Torrejón might involve Madrid itself in a Soviet nuclear exchange became vocal, and during 1958-59 there were high-level discussions with American authorities seeking withdrawal of American nuclear forces from Torrejón, but the United States refused to budge. "

The 1953 Concordat with the Vatican

"Such an arrangement was more eagerly sought by Madrid than by Rome, where the pope commented to visitors that the Spanish regime remained an arbitrary dictatorship, sometimes abusive of law and civil rights, and Spanish Catholics played a major role in convincing the Vatican of its desir- ability. Negotiations were begun by Ruiz Giménez, Francos ambassador to the Vatican from 1948 to 1951, and carried to fruition by his successor, Fernando María de Castiella, the rising star of the Spanish diplomatic corps.'? The concordat was finally signed in August 1953. It provided the fullest possible recognition by the Church, reaffirmed the confessionality of the Spanish state, and confirmed the existing right of presentation of bishops by the head of state. At the same time, it expanded the independence of the Church within the Spanish system, guaranteeing the juridical personality of the Church and the full authority of canonical marriage, and completed the restoration of the legal privileges of the clergy that had been partially abolished in the mid-nineteenth century. The Church would be exempt from all censorship in publications dealing with religious affairs, and Catholic Action groups would be allowed “freely to carry out their apostolate,” which had not always been the case." Virtually coinciding with the pact with the United States, the Concordat of 1953 marked another major step in the international recognition of the regime, even though most of its provisions merely ratified the existing status quo between church and state. "

"The obverse of state religious policy was the sharp restriction imposed on Spains nearly 30,000 Protestants. The 1945 Fuero de los Españoles guaranteed them freedom of private worship, but all public activity and announcements were prohibited.'* Moreover, Protestants were subjected to a variety of legal harassments, and there were occasional acts of arson and vandalism against their meeting places. "

"During the 1940s and 1950s Catholic schools not only regained but improved upon their earlier position within Spanish education. At their high point in 1961, 49 percent of all secondary students attended Catholic schools. Catholic publications also greatly expanded in number and volume. By 1956, 34 of the 109 daily newspapers being published in Spain could be defined as Catholic organs, and more than 800 other periodical publications were being brought out either by the clergy or Catholic lay associations. Subsequently, a new agreement with the state in 1962 freed official Catholic publications from prior censorship altogether, while certain Church officials continued to participate in concrete aspects of the general state censorship.

Growth in the number of religious vocations continued through the mid-1950s, as an all-time record number of new priests for the modern era (more than 1,000 a year) were ordained between 1954 and 1956. Yet certain signs of change began to appear by the late 1950s. A new mood of secularization began to emerge with economic expansion and the partial opening of Spain to foreign cultural and social influence. For the first time since the Civil War, certain indicators of popular devotion started to decline before the close of the decade. Though few observers might have credited it in 1953, the great secularization of the succeeding generation was already establishing its roots"

Relations with the Royal Family

"The uneasy compromise made by Don Juan with Franco in 1948 did give the royal family a certain privileged status in Spain, however, and during the 1950s the monarchists came to occupy the position of a sort of controlled and loyal opposition, concerned more to correct than to contradict the regime. The Madrid daily ABC, always the leading monarchist organ, was even allowed on one occasion in 1952 to attack Arriba, the central Falangist newspaper, "

"On July 16 Don Juan wrote to Franco that the appropriate time had come for the prince to pursue university study abroad in a high-caliber Catholic institution such as Louvain. This proposal apparently came from Gil Robles, who was eager to remove Juan Carlos from Francos clutches. The very next day, as it developed, Franco prepared a letter for Don Juan stressing that the time had come for Juan Carlos to gain more advanced training in Spanish institutions and that the appropriate course for a prince in line for the throne and the rank of commander-in-chief would be to matriculate at the Academia General Militar in Zaragoza, the institution first developed and commanded by Franco and then revived by his regime. Before he could dispatch this, Franco received the letter from Don Juan, to which he immediately and harshly replied in the negative. Rather than breaking with Franco, Don Juan gave in, provoking the resignation of Gil Robles as political advisor.

The next municipal elections in Madrid on November 24 attracted much more attention than usual, for they were touted as to some extent “free” elections in which for the first time one-third of the municipal councillors would be chosen individually by the direct, “inorganic” vote of heads of families and married women rather than exclusively by controlled corporate blocs. The only opposition permitted to enter alternate candidates for the four seats involved were the monarchists, whose nominees encountered harassment at every step from official institutions and young activists of the Frente de Juventudes and Guardias de Franco. Since this came to be regarded as a sort of mini plebiscite, the government pulled out all the stops, mounting a heavy press campaign and rigorously manipulating the vote on election day, after which it announced that the official slate in Madrid had won 220,000 votes, compared with 50,000 for the monarchist independents.** The blatant coercion nonetheless fully revealed the regimes fear of independent opinion, even in favor of conservative monarchists, and amounted to a public relations defeat.”"

The Military in the 1950s

"The officer corps remained a bloated 25,000, and the retirement age was the highest in Europe, making it superannuated as well. Though most older officers were on the preliminary reserve list, they still drew full pay. Franco was well aware of the waste and redundancy involved” and yet could never bring himself to impose a major reform, doubtless for fear of the political consequences. On July 18, 1952, provision was made for senior officers to take full-time jobs in civil service,” and in August the maximum age for officers and NCOs in active troop commands was reduced by two years. A second measure put into effect in July 1953 provided for the retirement with full pay and allowances of approximately 2,000 senior officers at the ranks of captain, major, and lieutenant colonel. The Army was at that point reduced from 24 to 18 divisions, and to little more than 250,000 men, which would remain its approximate troop strength for the next thirty years.

As early as January 25, 1952, the Ministry of the Army announced that Spanish small arms and artillery were being converted to accommodate United States weaponry and ammunition.” American military assistance between 1954 and 1958, the period of most intense allocation, amounted to about 350 million dollars, of which some 40 percent went to the Air Force and 30 percent each to the Army and Navy. The Spanish Air Force got its first jet fighters, and the acquisition of squadrons of heavy tanks made it possible to create an armored division, something that the Spanish Army had never possessed. Nearly 5,000 young officers and NCOs received advanced training in the United States during this period.” Interservice rivalry was kept to a minimum, partly because the Navy and Air Force were assigned specific and delimited roles and were so much smaller than the Army.

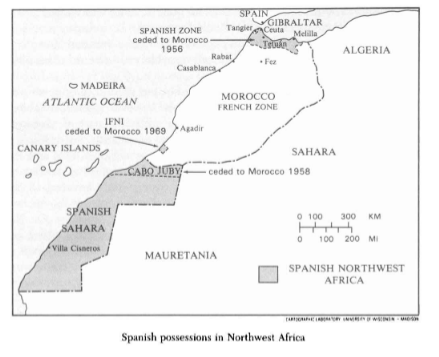

Since 1944, the primary concern of the armed forces had been domestic insurgency and subversion rather than repelling an external threat. Some of the annual maneuvers as well as the regular unit displacements and assignment of commands were directed toward this contingency, even though after 1950 such dangers were increasingly remote. The main external challenge from the early 1950s down to the very end of the regime and even beyond did not come from Europe or the Soviet Union but from the increasing difficulty of sustaining Spain's colonial position in northwest Africa.

The prime military problem for the last two decades of Francos life was Morocco. This was ironic, because the Generalissimo had made his reputation there and had retained a special emotional relationship with Africa, site of perhaps the happiest days of his life, ever afterward refracted in his memory through a youthful romantic glow. During the postwar ostracism,

the regime had emphasized a special opening to the Arab world and placed great emphasis on maintaining its position to Morocco. It was argued that Spains historical experience created a special relation to and understanding of Arab culture, and Spain in fact followed a somewhat more lenient policy toward native activities in its Protectorate than did France in the main part of Morocco. Yet in the final analysis native unrest sometimes had to be forcibly put down, and when all is said and done the only joint policy followed by both France and Spain during the period of ostracism was, in varying degrees, mutual repression of Moroccan nationalism.

Relations with the Arab world grew closer in the late 1940s and early 1950s, aided by Spains nonrecognition of Israel and a mounting antipathy toward the Jewish state after it had outspokenly voted for retention of the UN boycott against Spain in 1949. Hussein of Transjordan became the first foreign head of state to visit Spain since long before the Civil War. A Middle Eastern tour by Martin Artajo produced a variety of economic and cultural agreements, and Arab states were generally prepared to take a benevolent attitude toward Spain's role in Morocco. Since Moroccan nationalism was primarily directed against the French, Francos high commissioner after 1951, Lt. Gen. Rafael García Valiño, was able to follow a relatively lenient policy in the Protectorate. It was Moroccan pressure that won the reincorporation of Spain into the administration of the inter- national zone of Tangier in 1952.”

After the French government deposed the sultan in Rabat, the administration of the Spanish Protectorate continued to recognize him as the legitimate Moroccan leader, and García Valiño provided sanctuary for Moroccan nationalists in the Spanish Protectorate, which became a staging area for minor raids into the French zone. This bilevel Spanish policy was designed to discomfit the French and gain favor among the Moroccans, not to promote independence. Francos personal attitude seems to have been dominated by memories of how faithfully Moroccan troops had served under his command during the 1920s and later during the Civil War,” and he expressed the personal opinion that Moroccan independence lay in the distant future. Garcia Valiño was nevertheless unable to prevent a wave of nationalist strikes, demonstrations, and minor terrorist acts that broke out in the Protectorate late in 1955 and continued into the following year.

At that point Paris reversed its policy and prepared to withdraw, allowing a Moroccan nationalist cabinet to be formed in Rabat by the end of 1955. Three nationalists had earlier been given senior administrative positions in the Spanish zone and on January 13, 1956, the Spanish Council of Ministers agreed that independence would soon have to be negotiated with Morocco (with Franco privately blaming Garcia Valino for going too far in backing subversive activities against the French).” After France officially granted independence to its major zone in March 1956, the Spanish government—facing disorders in its own minor Protectorate— had no choice but to follow suit within one month. It was a bitter outcome for Franco, and it also meant the loss of the Guardia Mora, the mounted, gaudily dressed personal guard of specially selected Moroccans who had provided the brightest note in his personal entourage.

Sudden loss of the Protectorate was a bitter blow to the pride of senior officers, so many of whom had built their careers there. Military pay was again falling farther behind the spiraling rate of inflation, and restiveness began to appear among the military just as the first significant signs of dissent in five years emerged among the political opposition. General Antonio Barroso, who had recently replaced Salgado-Araujo as head of Francos Casa Militar, expressed the opinion that the officer corps was no longer as united as it had been several years earlier, for there was a feeling that the government was not responsive to problems and that ministers stayed in power too long.* Not long before the withdrawal from Morocco two cadets had been expelled from the Zaragoza military academy for de- facing a portrait of Franco,” and early in 1956 a number of small Juntas de Acción Patriótica were formed in garrisons at Madrid, Barcelona, Seville, Valladolid, and Valencia.” Though this might have been viewed as symptomatic of an alarming recrudescence of the military syndicalism and conspiracy that had plagued Spain in 1917—23, Franco responded in his usual calm manner, trivializing the phenomenon and virtually refusing to ac- knowledge it."

"The new Moroccan state coveted all the Spanish territories along its border, and the easiest target was the enclave of Ifni, surrounded on three sides by the land mass of Morocco. On November 23, 1957, Moroccan forces in the guise of irregulars, using formerly Spanish equipment provided their regular army, attacked Spanish positions in Ifni. A few small posts were overrun, but the invaders were stopped within three days. The Spanish garrison of 2,500 troops was expanded to 8,000 by December 9 after suffering 62 fatalities in the brief combat. The French also cooperated in the Spanish buildup, for Paris wanted to defend Mauritania to the south from further Moroccan expansion. Within a month the Moroccans “unofficially” struck again, this time attacking near El Aaiun, the capital of the Spanish Sahara. They were stopped once more, this time at the price of 241 Spanish dead. Spanish air strikes helped to turn back the assailants, and again France cooperated in the Spanish buildup. By February 1958 tranquillity was restored,* and the military had once more rallied firmly behind the regime in a time of crisis. The activity of the clandestine juntas quickly petered out.

Though these assaults did not for the moment pose a serious threat to Spain's remaining territories in northwest Africa, they were a violent indication of the strength of irredentism in Moroccan policy and raised serious questions for the future. The district of Cabo Juby, bordering Moroccos southern frontier, was ceded early in 1958, but the Spanish government intended no further concessions. Carrero Blanco was even more emphatic than Franco that both Ifni and the Sahara must be retained as a necessary strategic shield for the Canary Islands farther to the west. To strengthen their relationship with Spain, both territories were raised to the status of Spanish provinces on January 31, 1958, following the policy earlier adopted by Portugal for its own African possessions. Plans were announced for the emigration of 30,000 Spaniards to the largely barren and uninhabited Spanish Sahara, though little ever came of that. For the time being, the two Spanish-inhabited cities of Ceuta and Melilla were safe, but nothing had been done to extract a recognition of Spain’s sovereignty from the new Moroccan state at the time of independence, and the two cities were likely to become a major bone of contention in the future.

Through its policy of standing fast, the regime still upheld the military conception of Spanish honor, yet the place of the armed forces and the police in its financial priorities was steadily falling. The share of the armed forces in the state budget declined from 30 percent in 1953 to 27 percent in 1955, and then to 25 percent in 1957, whence it sank further to only 24 percent by 1959. The armed police, similarly, had become less numerous and costly by the late 1950s than under the Republic. Their total of 84,591 (with the Civil Guard) in 1958 was lower in proportion to the population than the number for 1935, and their share of the total budget had dropped from 6.3 percent in 1935 to 5.3 percent in 1958."

Falangism in the Fifties

"A prime demand by the democracies during the period of ostracism had been the elimination of the Falange from Spanish life. Franco responded by further deemphasizing the FET and altering part of the terminology and nomenclature of the regime, but the Falange as National Movement remained very much a part of the bureaucracy of the system, "

"The Movement was indispensable to Franco for several fundamental reasons. First, it provided a necessary cadre of leaders and manpower to staff portions of the regime. Secondly, it provided a modern social doctrine, was responsible for administering the syndical system, and had developed much of Spainss social welfare program. It also staffed the press and propaganda system and was responsible for the youth program. Finally, the Movement was the most loyal of Spanish institutions save for the military, because it had no other basis for its existence after 1945. It could even serve as a scapegoat” whose nominal downgrading would be evidence of reform and liberalization.

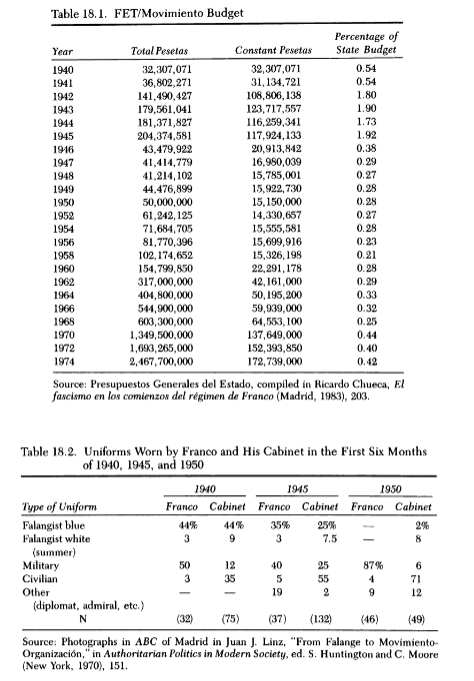

The FET' basic organizational budget had been cut drastically in 1946, when it was reduced by more than 75 percent. As indicated in table 18.1, Franco at first had not been willing to spend much money on the party, alloting it only a half of one percent of the state budget in the first two years after the Civil War. Once Arrese had taken over, this had been more than tripled for the four years 1942—45. After that, the party would never claim as much as a half of one percent of the state budget again and some- times only a quarter of one percent. The secondary role of the party was indicated by the fact that by 1950, if not before, Franco had almost ceased to appear in Falangist uniform (save for the annual party rally), though certain Falangist ministers occasionally did so."

"The security that the regime had achieved did permit a modest new cycle of Falangist political and cultural activity beginning about 1952, encouraged by Franco to counterbalance monarchism. When the able new satirical journal La Codorniz (The Quail, founded in the early 1940s in tongue-in-cheek imitation of Le Canard Enchainé)* published a satire in early 1952 of the Movements central journal Arriba (Upward) under the title Abajo (“Downward”), the regime allowed its offices to be sacked by Falangist toughs. "

"statements from various spokesmen also revealed continuing latent dissension within the organization between radicals and bureaucratic moderates, the former urging drastic statist economic measures.** The Congress provided an opportunity to blow off steam, for nothing more came of it. A large national rally could not mitigate the clear fact that the Movement, as a tame bureaucratic organization with scant initiative, failed to serve as a very effective vehicle of political mobilization and was becoming increasingly ineffective in the indoctrination of Spanish youth.”"

Cultural Differentiation and Conflict

"Though altogether lacking the financial resources to fill the many gaps in Spain's weak educational system, Ruiz Giménez held the initiative from 1951 to 1953, initiating reforms on both the university and secondary level. A new law of secondary education in 1953 partially revised the curriculum and also provided for limited inspection of Catholic schools. New university regulations established more impersonal and automatic procedures for the membership of qualifying boards (tribunales de oposiciones) for the nomination of professorial chairholders, eliminating some of the favoritism dominant since the Civil War. A major effort was made to re- incorporate highly qualified university faculty who had been ostracized, providing positions for such eminent professors as the exiled Arturo Duperier, Spains only internationally respected physicist.” Ruiz Giménez also encouraged liberalization of curriculum, choice of study matter, and cultural expression, which drew increasingly sharp attacks from Falangists and the extreme right.*'

Catholic pressure during this same period had also attempted to push a new press censorship law through Arias Salgado’s Ministry of Information and Tourism, since 1951 in charge of state censorship. The Junta Nacional de Prensa Católica initiated a new draft project that would have abolished prior censorship and would have been more liberal than the later reform carried out in 1966. It was much too free for the rigid Arias, a Catholic Falangist of the Arrese group, who quashed the project at the beginning of 1952. He was opposed to any overt change, and, remarkably loquacious for a censor, propounded at length in public speeches and articles what he liked to call “the Spanish doctrine of information,” which required prior censorship in most instances for the well-being of the nation.? Nonethe- less, despite the minister of informations reputation for rigidity, cultural and commercial contacts with western Europe and North America were expanding during these years, and greater diversity of opinion could be seen in Spanish publications, as the censorship made minor but broadening adjustments to accommodate the widening horizon of Spanish life.

A distinctive new Catholic influence had emerged by the 1950s in the secular institute Opus Dei (Work of God). Originating as a diocesan organization, it was the most unusual Catholic group in post- Civil War Spain and perhaps in the Catholic Church as a whole. Developing from a small nucleus founded by the Aragonese priest José María Escrivá de Balaguer in 1928, it was recognized in 1943 as the first secular institute in the Church. By the time that Pope John Paul II granted it the status of the Church’s first “personal prelature” in 1982, Opus Dei had expanded to a worldwide membership of approximately 72,000."

"During the first years after the Civil War members of Opus Dei were in general less closely connected with the regime than were those of Catholic Action. Its work seemed more progressive and modern than that of most other Spanish Catholic organizations of the 1940s, and thus it was supported and encouraged by several wealthy Catholic progressives, particularly in Catalonia. Falangists on the other hand attacked and opposed the institute and its members almost from the start.

Opus Dei came to the public's attention as scores of its members gained university professorships during the 1940s and 1950s. By the fifties some alleged that as many as 20 percent of the teaching positions in Spanish higher education were held by institute members, though that is probably an exaggeration.™ In 1952 Opus Dei opened what soon became the first completely developed Catholic university in the country, the University of Navarre at Pamplona. The organizations members came to prominence in business and financial affairs, and some developed an interest in politics, although others discouraged such activity.*"

"By 1954 rightist critics within the regime had effectively curtailed the freedom of action of Ruiz Giménez as minister of education, and the two brief years of limited apertura in educational and cultural matters were at an end. Nonetheless, by the mid-1950s the Spanish cultural panorama was broadening under the impact of expansion of the university system

and the growth of the economy, stimulated by new international and cultural relations. For the first time in the history of the regime university students, despite their nominal compulsory organization in the Falangist SEU, began to develop dissident ideas, whether from a critical Falangist, monarchist, independent catholic, liberal, or leftist perspective. By the mid-1950s the enforced consensus of Spanish cultural life was beginning to show its initial cracks."

The Crisis of February 1956

"In 1953 direct opposition among university students led to the first attempt to contest SEU elections when a new circle called Juventud Universitaria (University Youth) tried indirectly to resurrect the essence of the old Republican Federación Universitaria Española. Though this was not successful, a turning point of sorts was reached on January 27, 1954, when the SEU mobilized a student crowd, as it did from time to time, to protest British control of Gibraltar. The demonstration took place in front of the British embassy on the occasion of a visit of Queen Elizabeth to the colony, but for reasons that are not clear, the armed police charged the student crowd near the end of the protest, breaking it up violently. This led to a direct clash between the students and the police, followed by a spontaneous new counterdemonstration in the central Puerta del Sol demanding the ouster of the national police chief.* The authorities’ apparent betrayal of an organized patriotic protest helped to destroy much of the SEU’s remaining legitimacy. This was the last student mob ever mobilized by a government agency, and from that time opposition in the country’s largest university became more overt."

"The sense of frustration and artificiality was at that point even keener among many Falangists, relegated to a limited and secondary role and forced now to accept, at least in theory, monarchist principles which they had always combatted. Moreover, Francos own instructions that the Movement must become more monarchist seemed only half-hearted, for the Movement press (split off from the vicesecretariat of popular culture since 1945) continued intermittent attacks on the institution of monarchy and indirectly on the royal family.

Falangist resentment was expressed in two new efforts to form dissident, semiclandestine groups between 1952 and 1954, both soon repressed by the police.” The crisis of Falangism was most acute among the youth, and in January 1955 two of the principal Falangist youth publications came out with strong articles against the monarchy. "

"By 1956, at least four different small dissident student groups could be identified at the University of Madrid, in addition to the core Falangist minority of the SEU. At the extreme left was the clandestine Communist group, seeking to encourage militant opposition. There was also a very small Socialist group, formed in part around Rafael Sánchez Ferlosio, son of the Falangist writer Sánchez Mazas. Another small set followed the now ex-Falangist writer Ridruejo® and sought a drastic reform, though not necessarily the overthrow, of the system, while a dissident SEU group simply wanted to reform the existing SEU."

Free student elections were a prime goal, and on February 1, 1956, an oppositionist student manifesto was distributed calling for an elected na- tional assembly of students. Official SEU candidates were then defeated for the first time in elections for the minor office of sports delegates within the Faculty of Law, principal hotbed of dissent."

"It is doubtless true that, as La Cierva has suggested,” Franco was well enough informed to realize that the February incidents involved mere handfuls of politicized youth who could be easily repressed. At first hefailed to react, spending the tenth on a hunting trip, to the disgust of his cousin Salgado Araujo.” Not until one day later did the government decree for the first time the suspension of articles 14 and 18 of the Fuero de los Espanoles, followed by temporary closure of the University of Madrid. Moreover, the Generalissimo could not ignore the internal decomposition and mutual conflicts of the veteran political families of the regime, some of whom were nearing exhaustion. The loyal Girón warned

that there was considerable anti-Franco sentiment within the Movement.” It was obvious that Fernández Cuesta had been unable to maintain order among Madrid Falangist Youth, while would-be reformers within the Movement were a dangerous unknown quantity. The chief innovation of the current government, Ruiz Giménez’ attempt to open up and reform education, had drawn intense opposition and eventually the hostility of Franco himself. Extreme right-wing Catholics in the cabinet such as Arias Salgado or the Carlist Iturmendi could offer little new political support of their own. One alternative might be to bring in more technical experts, something favored by Carrero Blanco, but in the winter of 1956 Franco was not willing to consider any major change.

Thus after one week, on February 16, Franco carried out a very limited cabinet realignment to replace the two ministers whose authority had been most directly challenged. The Caudillos most trusted Falangist, Arrese, was brought back after eleven years in the wilderness to replace Fernández Cuesta as secretary general of the Movement, and the portfolio of Ruiz Giménez in Education was given to Jesús Rubio García-Mina, a university professor and former subsecretary of education...

This reorganization was carried out against a background of mounting economic distress brought on by persistently high inflation. The government granted a 20 percent across-the-board wage increase for Spanish labor on March 3, followed by another 7.5 percent in the autumn. To satisfy the military, who had been losing proportionately even more to price rises, an even greater increase—especially for junior officers—was given in the summer. Such measures did not head off major strikes in the Basque provinces in April, the first large-scale labor stoppages there in five years.”

Altogether, the crisis had been more significant than Franco's measured response indicated, for it was the regimes first major internal crisis in fourteen years, and the threatened Falangist “night of the long knives” had at least temporarily evoked widespread fear in Madrid. Moreover, the whole course of events had demonstrated that after fifteen years the regime was losing control of youth in the major universities, where previously it had had either limited support or at least uncontested domination. During the remaining two decades of Francos government, opposition in the larger universities would mount steadily. In addition, those of the “critical Falangist” and “progressive Catholic” intelligentsia ousted with Ruiz Giménez would never return to the fold but would henceforth remain outside the regime. The events of 1956 marked the first glimmerings of a new, internal opposition, one that stemmed not from the Republic or the emigrés of the 1940s but from the new generation who had begun to grow up under the regime during the 1950s"

The Abortive Falangist Fundamental Laws of 1956

"There is no indication that Franco had any major changes in mind after the February crisis other than tighter administration. The new secretary- general of the Movement, however, realized that the malaise of the Falange would be difficult to resolve merely through bureaucratic manipulation. He had opposed the entire monarchist direction of the Fundamental Laws in 1945-47” and believed that he might now be facing the last chance to guarantee a major role for the Movement in the permanent structure of the regime. Abortive projects for the institutional redefinition of the system were not unprecedented; drafts had been prepared during the 1940s by Serrano Súñer and by at least two other theorists that had come completely to naught. Arrese was nonetheless surprised and delighted to receive approval when he proposed to Franco that he assemble a new Falangist commission and prepare the text of possible new fundamental laws to redefine the role of the Movement.”"

"A meeting of the Junta Política on May 17 approved a commission under Arrese to prepare draft projects of new fundamental laws to redefine the Movement, its principles, and its role in the system...who presented a draft in June that would not only have given the National Council a dominant institutional position but would also have reorganized the Cortes on a partially direct elective basis. Offices within the Movement would have been made directly elective on the local level and indirectly elective on higher levels. Such extensive loosening of control was obviously impossible, and after a stormy argument González Vicén resigned.*

By autumn three draft projects had been prepared dealing with the principles of the National Movement, a new organic law of the National Movement itself, and a proposed law of government organization (ordenación). The first seemed to provoke little controversy, for it carried out a drastic defascistization of the original Twenty-six Points of the Movement. Its four articles dropped all references to empire or any other radical goal, stressing instead the principles of Catholicism, the family, state syndicalism, integrity of the individual, national unity, and international cooperation. The National Movement itself was defined as “an intermediate organization between society and the state and a means of integration of public opinion.”

The proposed Organic Law of the Movement was much more drastic, for its terms would have made the Movement absolutely autonomous to the point of independence after the death of Franco, with great power concentrated in the hands of its secretary general and National Council. The chief of state after Franco would hold no direct position of leadership in the Movement, though members of the National Council would bpartly appointed by him and partly elected by the Movement. Future secretaries general would be elected by the National Council and then named (in effect, ratified) by the chief of state, and would be responsible only to the council. The council would hold the power of a court of constitutional review and could declare invalid any legislation under consideration by the Cortes. It would also be empowered to transmit its recommendations on policy, legislation and administration to the government. The proposed Law of Government Organization was intended to give the Movement a dominant role in the functioning of the government. It provided for the chief of state to appoint a separate president of government (prime minister) after consulting with the president of the Cortes and the secretary general of the Movement. The latter would automatically become vice-president of government at the time of Francos death, should the latter office then be vacant. The president and his cabinet would serve for a term of five years, removable at the order of the chief of state or three adverse votes by the National Council. The secretary general was endowed with a perpetual legislative veto as a member of cabinet, for his abstention or negative vote on any issue would trigger a vote of confidence in the government by the National Council. The Cortes, by contrast, was only empowered to censure individual ministers, and its vote could be negated by an expression of confidence by the National Council. The latter would thus become an executive senate with veto power over a future prime minister and all subsequent legislation. More- over, none of these documents ever referred to either the monarchy or the king.

In this fashion Arrese and the old-guard Falangists hoped to perpetuate a new political monopoly for the party after Franco's death. The new ambition that Arrese injected into the party resulted in a flurry of new adherents; approximately 35,000 new members joined the Movement in 1956, its last significant increase. Arrese hoped that neo-Falangist doctrine, totally rejected by social democratic western Europe, might still exert influence in the Middle East,* where the Spanish regime enjoyed friendly relations with Arab nationalism.

Most members of the regime hoped for a formula that could maintain basic features of the system after Francos death, but none save core Falangists would support a proposal to give such permanent power to the secretary general and National Council of the Movement. Monarchists objected particularly to the exclusion of any mention of the Crown, and the more reform-minded also objected to the power granted a future chief of state.2 "

"Though not a word appeared in the press, copies of Arrese’s draft projects circulated widely among the regimes elite, and opposition mounted from all sides. Some of the top military commanders expressed objections, and the monarchist minister of public works, the seventy-year-old Conde de Vallellano, distributed two documents during October denouncing what he termed introduction of a “totalitarian state” and an “oriental-style politburo,” emphasizing that “to declare dogmatically in a legal document that the political ideas of the Falange represent in a permanent manner the political will of the Spanish people is objectively absurd.’*"

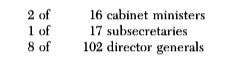

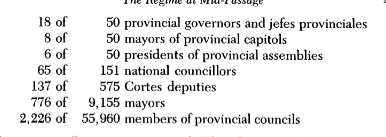

"Arrese at first refused to give in. To underscore the absence of any Falangist domination or even broad influence under the regime to date, he prepared data for a report to the National Council on December 29, 1956. It concluded that in the current Spanish political structure, camisas viejas of the party had only the following representation in government:"

"“That is to say,” Arrese commented, “that the original Falange occupies approximately 5 percent of the posts of leadership in Spain.”

Since Franco had instructed him to revise each of the proposals over the Christmas vacation, Arrese tried to interest the Caudillo in watered- down versions of the two principal projects. In the final version, the National Council would merely form part of a new Court of Constitutional Guarantees, sharing power equally with the Council of the Realm. To assuage the cardinals’ wrath, a faint proposal for greater representation was advanced in the form of new Hermandades (brotherhoods) that could be organized within the Movement to correspond to the various groups that had originally composed it during the Civil War. As it turned out, Franco found none of this acceptable.

Ever since the preceding summer there had been talk of a general government change, and Arrese had been working toward an expansion of Falangist influence in the cabinet. By that time, however, Franco was more concerned about the continued inflation and heavy balance of payments deficit, which was becoming a severe problem. The regime needed better economic leadership, while any reaccentuation of Falangism had become futile and anachronistic and was clearly unacceptable to the major institutions and currents of opinion in the country. A more detailed and complete new elaboration of fundamental laws might be desirable, but that would have to be postponed until they could be prepared under different terms and more acceptable patronage than that of the Movement. The present climate of Spain and of international opinion instead required efficient technical administration, something that the Movement itself was unprepared to provide. In February 1957 Franco decided to shelve the Falangist proposals sine die and carry out a broad new cabinet renovation.”"

The New Government of 1957: Toward Technocracy and Bureaucratic Authoritarianism

"The key new appointees were mostly professionals with university or technical backgrounds, though here almost for the first time Franco en- countered one or two refusals. Carrero Blanco exerted rather more influence than before, anxious to shortcircuit the Falange and bring in experts capable of reorganizing state administration and carrying out a more efficient economic policy, although Arrese may also have played a role in bringing one or two of the new people to Francos attention.

The three key technicians in economic affairs and state administration were all members of Opus Dei and had the direct backing of the subsecretary of the presidency. "

"These three new appointees would be responsible for conceiving and executing the major changes in Spanish economic policy during the next two years (treated in the following chapter), though it is more than doubtful that Franco had any alterations of such magnitude in mind when he assembled the new government.

Franco saw to it that Falangists retained four posts...hus Falangist representation in government was not numerically diminished, but this did not disguise the fact that the withdrawal of the reform projects and the main thrust of the cabinet realignment represented a fundamental defeat for the Movement and the start of its final deemphasis. Arrese held his new post for only three years before resigning and retiring altogether from public life"

"Franco changed his military ministers more frequently than any others, probably in order to avoid having any general consolidate too much personal power or influence."

"he took some satisfaction from two major European events of the following year which he saw as a kind of vindication of the need for strong government. Visiting a new industrial complex at Cartagena in October, he hailed the first Soviet space vehicle Sputnik as “something that could not have been achieved in the old Russia’ (in his customary ignorance overlooking the fact that under the old semiliberal regime Russia had in fact made several early aeronautical breakthroughs)because “great accomplishments require political unity and discipline. Such unaccustomed praise from the senior anti-Communist of Europe was intended as a vindication of authoritarianism, regardless of political hue. The second development, even more applauded by Franco, was the collapse of the parliamentary Fourth Republic in France and its replacement by a presidential Republic under Charles de Gaulle, who also affirmed, though in quite different terms than Franco, that the party system did not work.'”"

"The new government made its own limited contribution toward further institutional definition by finally enacting a new version of the Principles of the Movement, promulgated on May 29, 1958. These completely replaced the old Twenty-Six Points and, similar in part to the earlier draft by Arrese, were fully sanitized of any overtly fascistic expression. They affirmed patriotism, unity, peace, Catholicism, the individual personality, the family, representation through local institutions and syndicates, and international harmony. Reflecting Carlist rather than Falangist concepts and terminology, the Movement was termed a “communion’ instead of a party, and the regime itself defined as a “traditional, Catholic, social, and representative monarchy. ' In one of his more notorious personal inter- views a few days later, Franco told the French journalist Serge Groussard that he had never been influenced by anyone, not even Mussolini, and that he had “never” contemplated entering the war on Germanys side. “I also am” a democrat, affirmed the Caudillo, referring to his own nominal concept of organic democracy.'

The traditional leftist opposition, broken by the events of the late 1940s, would never fully recover during Francos lifetime. Neither the passage of the dissident ex-Falangist Dionisio Ridruejo into outright opposition'™ nor a major new strike wave in Asturias and Barcelona during March 1958'® had much impact, though these were the most extensive strikes since 1951. The government responded by suspending nominal civil rights and declaring an estado de excepción (constitutional state of exception) for four months. Similarly, radicalization of clandestine student politics at the leading universities was growing apace but would not become a problem until the following decade. Major initiatives by the Spanish Communist Party failed completely. Its declaration of a Jornada de Reconciliación Nacional (Day of National Reconciliation) for May 5, 1958, which was to have been accompanied by local strikes and transport boycotts in many parts of Spain, attracted little support, while the following Huelga Nacional Pacífica (Peaceful General Strike), scheduled for June 18, had little support beyond the small groups of workers directly influenced by the Party. '

New measures were nonetheless taken to tighten police controls. A law of March 22, 1957, specified that in the case of collective illegal activities such as strikes, when it was not possible to identify directly those primarily responsible, persons in positions of responsibility or with seniority among those involved could legally be charged instead. On January 24, 1958, a new military court with special jurisdiction for “extremist activities” in all of Spain was established under the direction of Col. Enrique Eymar Fernández, who acquired a sinister reputation during the next decade. Franco felt it necessary to be fully prepared, indicating privately on June 9 that he had “direct information from the Masonic lodges” of “a campaign of great proportions against the regime.'” There followed a new redaction of the Law of Public Order (July 30, 1960), which provided that those arrested for strikes, demonstrations, and attacks on public utilities or supplies would be prosecuted before a special court of civil judges, and there was a new Law against Military Rebellion, Banditry, and Terrorism (September 26, 1960).

In fact, the number of those involved in opposition activities was quite limited, and according to the statistics of the Supreme General Staff, the annual total of those condemned by the special military tribunals was declining steadily. From 1,266 in 1954 it dropped to 902 in 1955 and again the following year, then to 723 in 1956 and to 717 in 1958, falling further to 529 in 1959.'* The ordinary crime rate in Spain was very low during these years, so that by 1959 the prison population stood at 14,890,"° compared with 34,526 under the Republic in 1935, when there were five million fewer inhabitants."